“Human zoos were not mere spectacles—they were instruments of colonial power, perpetuating racial hierarchies and dehumanization.”

1. Introduction to Human Zoos

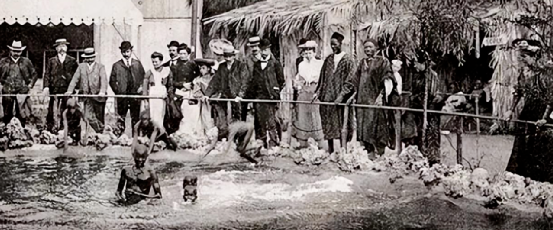

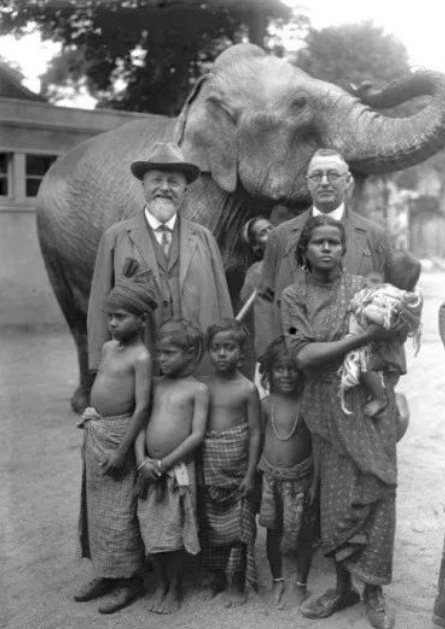

Human zoos, also known as ethnological expositions, were public displays of people—often indigenous or non-European individuals—presented as “exotic” or “primitive” curiosities. These exhibitions began during the Age of Exploration in the 15th century and persisted until as recently as 1958. Visitors paid to observe these individuals in staged environments, reinforcing harmful stereotypes of racial superiority and colonial dominance.

2. Origins and Evolution of Human Zoos

2.1 Early Beginnings (15th–18th Century)

- Vatican’s “Menagerie”: In the 16th century, Italian Cardinal Hippolytus Medici collected people from over 20 ethnic groups, housing them alongside exotic animals in Vatican gardens. This marked one of the earliest examples of human exhibitions.

- Colonial Exploitation: European explorers like William Dampier showcased tattooed individuals from Southeast Asia in London in the 1690s, branding them as “savages” to attract paying audiences.

2.2 The Rise of Commercial Exhibits (19th Century)

- Freak Shows and “Scientific” Racism: By the 1800s, human displays became commercialized. Shows like P.T. Barnum’s exhibition of Joice Heth (an enslaved woman marketed as George Washington’s nursemaid) blended entertainment with pseudo-scientific racism.

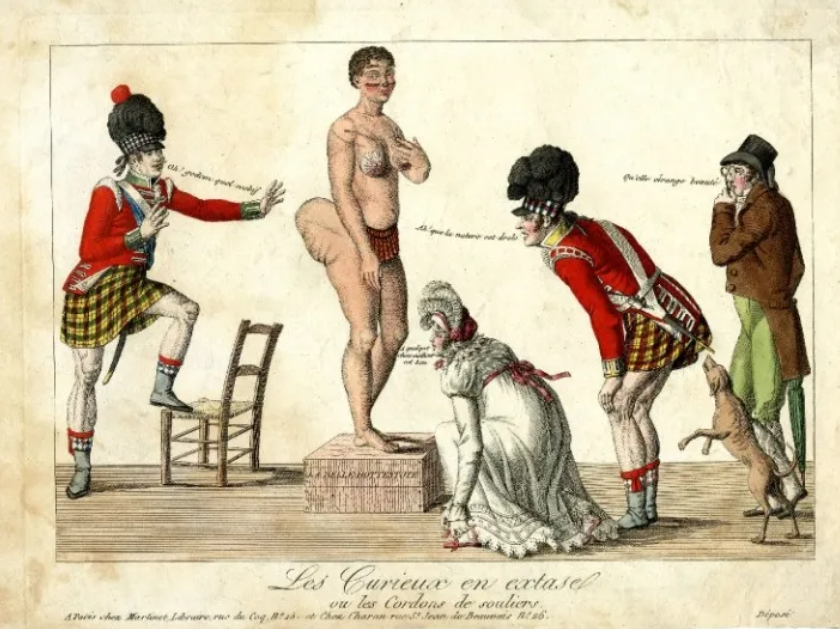

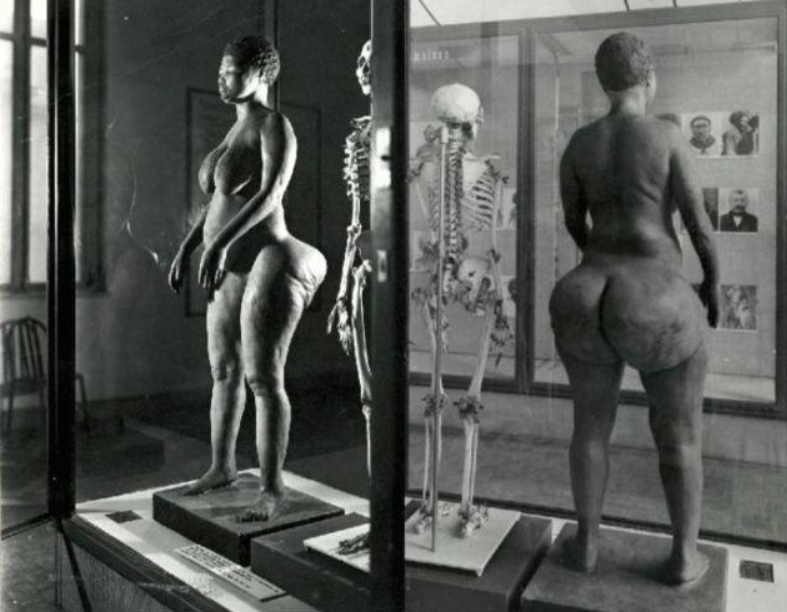

- Sarah Baartman’s Tragedy: A South African Khoisan woman, Sarah Baartman (1789–1815), was paraded in Europe as the “Hottentot Venus.” After her death, her body was dissected, and her remains displayed in Paris’ Musée de l’Homme until 1974.

3. Case Studies: Victims of Human Zoos

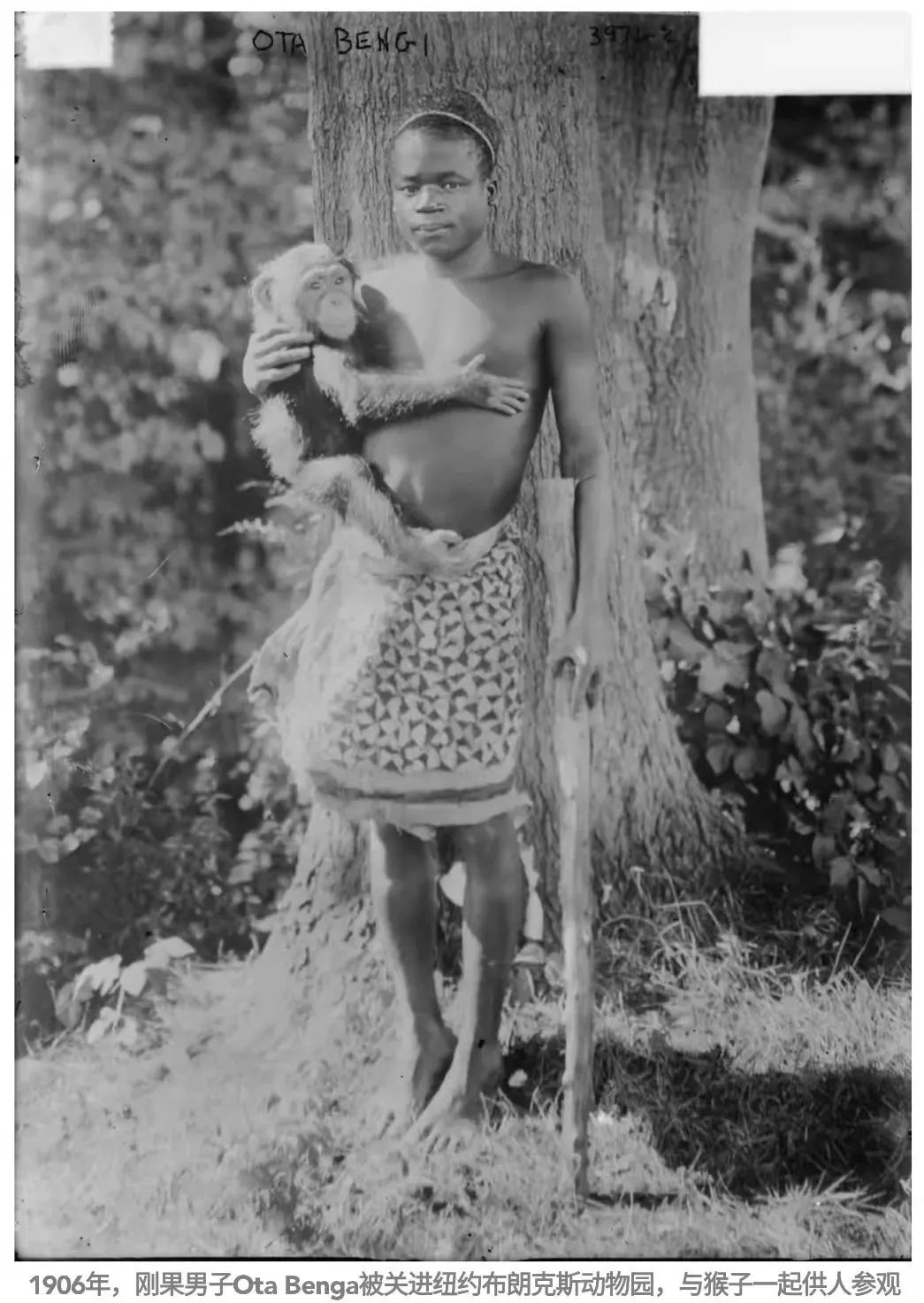

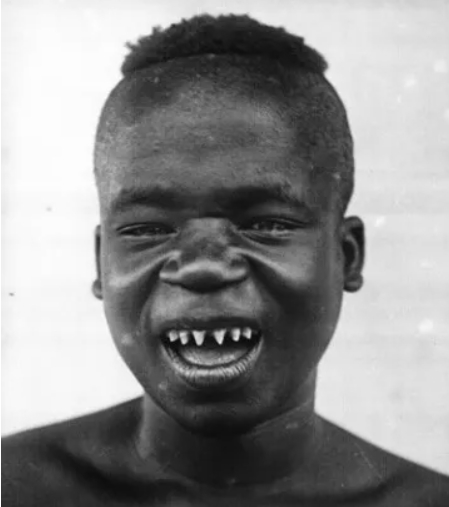

3.1 Ota Benga: The “Missing Link” in a Bronx Zoo (1906)

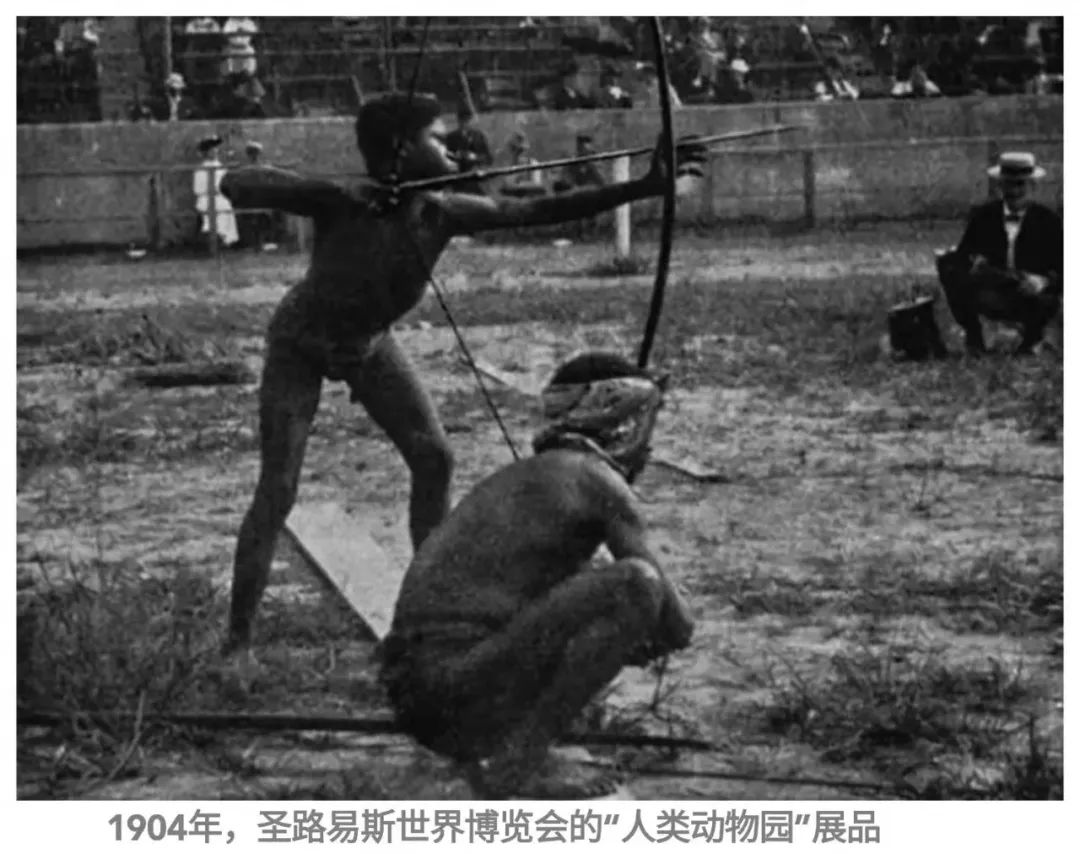

- Background: Ota Benga, a Congolese man, was purchased by missionary Samuel Verner for $5 and displayed at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Later, he was confined in the Bronx Zoo’s monkey house, labeled as a “pygmy” and a “bridge between humans and apes”.

- Public Reaction: Over 400,000 daily visitors mocked Benga. Protests by Black ministers eventually freed him, but he died by suicide in 1916, despondent over his displacement.

3.2 The Brutalization of Indigenous Women

- Sarah Baartman: Forced to perform nearly nude, visitors paid extra to touch her body. Her exploitation continued even after death, with her skeleton and organs displayed in museums.

- Afong Moy: A Chinese woman brought to the U.S. in 1834, exhibited as the “Chinese Lady,” where audiences paid to see her bound feet.

4. Expansion to Asia: Chinese and Taiwanese Victims

4.1 The Case of “Ah-Fong” (1842)

- Kidnapped and Displayed: A 19-year-old Chinese woman, renamed “Ah-Fong,” was exhibited in New York. Visitors paid 50 cents to view her bound feet and traditional attire. She died in captivity after severe abuse.

4.2 Taiwan’s Indigenous People at the 1910 London Expo

- Colonial Propaganda: Japanese colonizers showcased Taiwanese indigenous groups at a London “Human Races Exhibition,” framing them as “primitive” subjects of Japan’s empire.

5. The Last Human Zoo: Brussels’ 1958 World’s Fair

5.1 The “Congolese Village” Scandal

- Conditions: 273 Congolese men, women, and children were confined in a simulated “African village.” Visitors threw coins and bananas, treating them as spectacles.

- Global Outrage: Photos of a white woman feeding a Black child like an animal sparked protests, leading to the eventual end of human zoos.

6. Legacy and Modern Reckoning

6.1 Repatriation of Remains

- Sarah Baartman’s Return: After decades of activism, France returned her remains to South Africa in 2002. She was buried with national honors on Women’s Day.

- Museums and Accountability: Institutions like Paris’ Musée de l’Homme have removed displays, but debates continue over colonial-era collections.

6.2 Why This History Matters

- Colonial Trauma: Human zoos perpetuated dehumanization, justifying exploitation and racism. Their legacy influences modern discussions about reparations and decolonization.

- Silenced Narratives: Many victims’ stories remain untold. For example, Filipino groups exhibited in 1886 Spanish fairs or Inuit families displayed in 1880s Europe.

7. Conclusion: Remembering the Forgotten

Human zoos were not isolated atrocities but systemic tools of colonial power. From Sarah Baartman’s exploitation to Ota Benga’s despair, these exhibitions reveal the brutality of racial hierarchies. While formal human zoos ended in 1958, their echoes persist in modern racism and cultural erasure. Acknowledging this history is essential to building a more equitable future.

For further reading, explore archival records from the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition or the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair.